Philanthropy Vs. Capitalism: rambling towards understanding giving to charity

Ahead of a fundraising innovation workshop next week, I’ve been thinking again about the differences between philanthropic and capitalistic thinking for charities.

For the purposes of this rambling stream of thoughts about how charities can understanding ‘giving’ in a different way, here’s some definitions:

Philanthropy: private initiatives, for the public good.

Capitalism: private initiatives, for the private good.

(For completeness, Government is public initiatives for public good)

From a Charity (big ‘C’: organisation with charitable aims, rather than small ‘c’: being charitable) perspective, philanthropy is a one-way value exchange, meaning supporters pass value, mostly through financial donations to the charity but don’t receive any value in return. And capitalism is a two-way value exchange, meaning customers pass the value of their cash to an organisation or other person in return for receiving the value of goods or services.

Capitalism, as the dominate economic model in western society, has lots of history and theoretical models behind it to help us understand it and apply some of that thinking to charity fundraising, but first where did philanthropy come from?

Where does making charitable donations come from?

Financial donations to charitable organisations was fashionable among the middle classes in the 19th century, and through the twentieth century, with the shift in social classes and social mobility, making donations became something other classes did too.

This means that the making of charitable donations has always been very closely connected to social class.

The BBC class survey showed the class make up across the UK as:

- 6% Elite – the wealthiest and most privileged group in the UK

- 25% Established middle class – the most gregarious and the second wealthiest of all the class groups.

- 6% Technical middle class – a small, distinctive and prosperous new class group.

- 15% New affluent workers – this group is sociable, has lots of cultural interests and is in the middle of all the class groups in terms of wealth.

- 14% Traditional working class – this class group scores low for economic, social and cultural factors, but they do have some financial security.

- 19% Emergent service workers – this class group is financially insecure, scoring low for savings and house value, but high for social and cultural factors.

- 15% Precariat – this is the poorest and most deprived class group.

Understanding social class is important in understanding charitable giving as class is made up of income, education, social networks, and social contacts, and all of these things that affect a persons ability and proclivity to donate.

Donating is a social act.

What makes people donate?

Reasons for donating to charity can fit into three broad categories:

- Purely altruistic – motivated by supporting the good done by the charity.

- Impurely altruistic – motivated by the expectation of getting some value from knowing they have contributed to the good for the charity.

- Not altruistic – motivated by wanting to show friends and family that they are a ‘good’ person.

Charities assume, under the philanthropic model, that all charitable giving is ‘purely altruistic’. Capitalistic thinking might say that pure altruism is a myth and that a donor is always motivated to derive some value, even if it’s just feeling like a good person.

Supply and demand in charitable fundraising

“In microeconomics, supply and demand is an economic model of price determination in a market. It postulates that, holding all else equal, in a competitive market, the unit price for a particular good, or other traded item such as labor or liquid financial assets, will vary until it settles at a point where the quantity demanded (at the current price) will equal the quantity supplied (at the current price), resulting in an economic equilibrium for price and quantity transacted.”

The same thinking could be applied to the supply of fundraising products by charities against the demand from impurely-altruistic and not-altruistic supporters. In this context ‘price’ means the value derived by the customer.

Quantity of fundraising products in the market

If there are fewer causes to donate to (either perceived or actual), the value of those causes increases. The value here can be thought of in terms of greater awareness for supporters and so an increased propensity to donate.

The more ‘asks’ that are put in front of supporters, the lower the value of those asks. A flooded market is no good for charities or supporters as it drives down the value of each fundraising product.

Imagine a world with perfect social equality, no environmental damage, and no disease or life-threatening health conditions. The majority of charities would have no reason to exist. Those that managed to find a reason would operate within a high demand market, pushing up the value of their fundraising offer.

Value of fundraising products in the market

This is where social contracts/act of donating comes in. If making a donation meets the needs of affirming a donors values, triggers empathy and connection, allows to let people know they’re doing a good thing, etc., then it has a higher value in the market than an ‘ask’ that doesn’t deliver these benefits.

Would you rather donate £10 anonymously to provide massages for stressed businessmen in Tokyo or to provide nurses for sick children in your local town and be able to post about it on Facebook? Option A doesn’t meet the social contract of donating and so has low market value, whereas option B has a higher market value as it includes aspects of the social contract.

The right number of asks giving the right value return equals equilibrium and so optimisation for the fundraising offer.

However, it often seems that charities, working under the philanthropic model, do a lot of work in trying to get the ‘ask’ right; creating new campaigns, testing images, optimising donation forms of web pages, etc., but do very little about delivering value to the donor. Made a donation? Here, have a thank you letter. Not a great value exchange, if you think about it from a capitalist point-of-view.

So, charity fundraising as an industry, charities, and those who work in fundraising, need to shift away from the idea of philanthropy as one-way value from donor to charity, to capitalism as a two-way value exchange between donor and charity. Once this kind of thinking is embedded, then they can start asking the question: what do donors really want in return for their donation.

Blockchain for charities, a talk by Rhodri Davies

Why should charities care about Blockchain?

- Blockchain offers new ways for charities to achieve their mission.

- Blockchain will change the way organisations operate.

- Blockchain may create new problems to be addressed by charities

Charities don’t have the luxury of thinking they can get away without thinking about disruptive technology.

Charities need to understand the nature of the changes Blockchain will cause or become irrelevant.

Disruptive = doing stuff in a way that makes the old way obsolete.

Cryptocurrency & Blockchain Technology

Non-financial blockchain uses

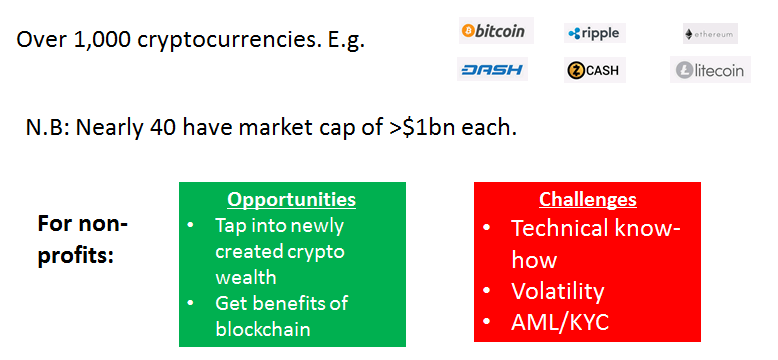

Cryptocurrency

What are the key feature of blockchain tech?

What does blockchain enable?

Civil Society Blockchain Possibilities (part 1)

Civil Society Blockchain Possibilities (part 2)

Testing images for charities

A selection of our images and stock images were tested and this is a summary of some of the outcomes:

- People look at facial expressions, especially mouths.

- People facing towards the camera offer better impact and being able to see their eyes to gauge emotion is useful.

- Images with a clear purpose resonated, for example seeing someone wearing a branded T-shirt helped better connect with a fundraising ask or gave that sense of wanting to help. People wanted to be able to visually identify a charity and will look for badges and logos.

- When showing a survivor, provide clear visual clues such as scars from surgery.

- Don’t use shots of people wearing high-fashion (really well-dressed people) as apparently this is off-putting.

- Don’t show images that could bring people to do the opposite of what you want, e.g. someone eating chocolate when we would want them to abstain –we’re not good at processing negatives.

- Show images with hope, not shame – people connect emotionally.

- Staged images weren’t well received – such as a baby dressed up in a Santa outfit. People felt manipulated. There is a fine balance between making people feel bad about themselves, against tapping into emotion to prompt people to react and donate.

- Images showing concern makes people want to take action, but with a medical image of someone with discomfort made people turn away.

- Natural poses and settings make people identify and comes across as warm and genuine.

- Selfies did not read well, as people in them did not comes across as connected to cause.

- Everyday people were more relatable – not super-fit super models.

- Moments at the end of the race and demonstrating a sense of achievement were well received (rather than mid-race, partway through ‘the struggle’).

- Groups of people / crowds tested well.

- Images of babies tested better than of older children to show a sense of urgency and to prompt donations, as did black and white photography.

- Real (recognisable) medical equipment tested better than graphics – and even more so if in use in a realistic setting such as a hospital.

- To demonstrate ‘money making a difference’ images of researchers tested better than images of survivors as the latter give the impression of helping ‘only one person’.

- Showing several researchers working rather than a single researcher gave the impression that more was being achieved.

Charities have to choose unsolvable problems

The biggest risk to a charity is solving the problem they set out to solve. If they solved it there would no longer be any reason to exist. So the aim for a charity is not to solve its chosen problem but just to make progress towards a solution. This is why charities have to choose unsolvable problems.

The removal of digital

I read Robert Green’s blog post about digital getting out of the way for fundraising and not using the term ‘digital’ in team names.

It reminded me something an old manager of mine said, “One day, having a social media team will be thought of in the same way as having a telephone team”. He meant that everyone has a telephone on their desk and knows how to use it, and that social media and using it to talk to customers would be something everyone in a business does, it wouldn’t be owned exclusively by a single team.

Whilst I’m not sure social media teams would agree as arguably social media platforms have gotten more complex since then, the point is easily transferable to ‘digital’.

Digital is a mindset and a skillset that everyone who works in a twenty first century business should possess. Organisations may take the same approach as CRUK and choose not to have a separate digital team, such as Halfords which split it’s digital team and joined them with the IT and Marketing departments. Or organisations may use a hub and spoke model with a core digital team doing customer-facing digital activities such as website development and performance marketing, but with the intention to push out digital skills into other parts of the organisation. Or an organisation could choose to have a single central digital team who manage all the digital activities for the organisation.

And perhaps, as Robert suggests, you can measure an organisations digital maturity by the model it uses. A really digitally mature organisation just does ‘digital’ without even thinking about it as separate from doing ‘reporting’ or doing ‘writing’ or doing ‘customer service’. I remember a few years ago, CRUK’s head of digital as he was then, saying that he wanted the people at CRUK to be as digital at work as they are at home. No one sits and home, switches off the TV, and thinks, “I’m now going to be ‘digital'”, as they put Netflix on, they just do it. Maybe removing ‘digital’ from team and role names is big part of being as digital at work as at home.